Electricity privatisation in Victoria

Monday 19 Jan 2015The consequences of the extensive privatisation of Victoria’s electricity system were made tragically apparent during the Royal Commission into the Black Saturday bushfires, which found that faulty power lines were responsible for five of the most devastating fires.

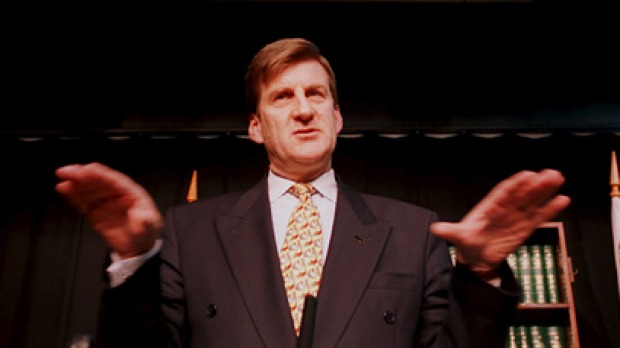

Victoria’s electricity system was privatised in the 1990s by the Kennett Government, as a part of a program to pay off government debt.

Before beginning the privatisation process, the Kennett government imposed a 10 per cent increase in electricity prices. As a result, the profitability of the industry and the attractiveness of assets to buyers, were enhanced. In line with the requirements of NCP, structural separation was imposed on the industry, breaking the integrated State Electricity Corporation of Victoria (SECV) into a large number of separate firms.

The major power stations, Loy Yang A and B, Yallourn and Hazelwood were sold separately. The distribution and transmission sector was broken up into six firms: Eastern, Powercor, Solaris, CitiPower, United, Powernet. In common with the approach used elsewhere in the NEM, retail activities were initially allocated to the distributors.

Initial evaluations of the privatisation were generally positive, reflecting both the dominance of market liberal thinking and some apparently favourable short-term outcomes (Institute of Public Affairs 2000). The prices received for the electricity assets higher than was expected on the basis of past privatisations. Moreover, deregulated prices offered to large customers were well below those that had been charged by the SECV. The expectation was that full contestability, introduced in 2002, would extend similar benefits to small business and household customers.

In reality, the low prices offered in the early stages of market contestability proved to reflect the incentives inherent in the NEM to run down reserve capacity (criticised at the time as ‘gold plating’). Private owners cut back on new investment, particularly in system reliability. By the time full contestability arrived in 2002, there was little excess capacity left. Household and small business consumers, who lost access to publicly regulated prices at this time, faced increases in prices, which accelerated over time.

In the subsequent decade, outcomes for consumers have become steadily worse, as elsewhere in Australia. Under privatisation and corporatisation, electricity distributors have been unwilling to invest in new network infrastructure unless they are guaranteed high rates of return. This had tragic consequences for victims of the Black Saturday bushfires.

The same pattern has been observed in other privatised infrastructure industries, such as ports, airports and telecommunications. Private owners have been able to realise cost savings in operating capital assets purchased from the public sector (often by reducing wages and working conditions). But they have consistently failed to deliver new capital investment at a cost comparable to that of the public enterprises they displaced.

Quiggin (2003) concluded that estimates of the fiscal benefits had been overstated, and that the sale was at best neutral in fiscal terms. The core of the analysis in Quiggin (2003) involved projecting the earnings of the SECV under continued public ownership based on its published business plan for the first ten years, and constant earnings thereafter. The discounted value of earnings was estimated at between $20 billion and $30 billion, compared with a sale price of $20 billion.

Using the information in the SECV business plan, it is possible to estimate the value of the earnings the SECV would have generated in continued public ownership. For this purpose it is assumed that the productivity and price changes in the business plan would have applied for a period of ten years, after which earnings would have remained constant in real terms. The net present value of earnings is calculated using a real discount rate of 4 per cent, which is about equal to the average real interest rate on government bonds for the period, though slightly higher than that used by the Regulator-General. (The effect of using a higher rate is to reduce the value of the enterprise in continued public ownership.) To test the sensitivity of the analysis to the discount rate, an alternative rate of 6 per cent is also used.

At a real discount rate of 4 per cent, the present value of the earnings of the SECV under the business plan scenario would have been around $30 billion. At a discount rate

of 6 per cent, the present value falls to $21 billion, a little more than the amount actually realised when the assets were sold This is consistent with the observation in the introduction that the reduction in interest payments on public debt achieved as a result of privatisation was about equal to the earnings foregone.

Quiggin (2003) concluded that the fiscal results of privatisation was roughly neutral, and observed: Compared to other instances in which governments have sold public infrastructure or government business enterprises providing infrastructure services the neutral impact observed from the privatisation of the Victorian electricity industry is relatively favourable. Most such privatisations and private infrastructure deals, including Victorian examples such as the CityLink project, have generated substantial losses in public sector net worth.

Three main factors explain the relatively favourable outcome of electricity privatisation in Victoria. First, the privatisation process was designed to maximise fiscal returns, whereas many privatisations have been focused on a range of political objectives, some of which are mutually inconsistent. Second, the Commonwealth government subsidised the deal. Finally, and most importantly, the buyers paid too much. In particular, the buyers of regulated transmission and distribution assets clearly expected more favourable treatment from regulators than they actually received.

Subsequent experience suggests that the losses from privatisation have increased since the analysis of Quiggin (2003) was undertaken. Most importantly, the regulated charges for distribution monopolies, which were held down in the early years following privatisation, have been increased drastically, with the aim of encouraging new investment. As a result, retail prices have risen sharply, as have the profits of electricity distributors.

In addition, the massive human and physical cost of the bushfires caused by poorly maintained privatised power lines must be taken into account.

This analysis is taken from Electricity Privatisation in Australia – A Record of Failure, published in February 2014 by John Quiggin Opinion and Consulting and commissioned by the Victorian Branch of the Electrical Trades Union.

Learn more about the electricity privatisation disaster in Victoria: